The Business Lobby and the Tea Party

David Cote is the CEO of Honeywell, a technology conglomerate and defense contractor that also dabbles in energy. In 2012, he clocked in at number five on the Forbes list of the highest paid CEOs, with an annual compensation in the ballpark of $55 million.1 Named CEO of the year last year by a publication called Chief Executive, he would seem to be doing quite well.2 Yet Cote these days is an anxious man, concerned about the future of American politics.

What troubles Cote is the Tea Party—specifically, the Congressional caucus associated with the Tea Party which was able to shut down the government and bring the country to the edge of default last fall. In the past, Honeywell’s political action committee (PAC)—the seventh-most generous corporate PAC in the nation—had been a prominent funder of conservative Republicans.3 But in the midst of the fall crisis, Cote was one of a number of executives and business lobbyists to publicly denounce the intransigent Republicans in the New York Times, saying it was “clearly this faction” that was to blame for the impasse.4 Earlier in the year, he told the Times that he stood squarely behind President Barack Obama: “You should not be using the debt limit as a bargaining chip when it comes to how you run the country. You don’t put the full faith and credit of the United States at risk.”5

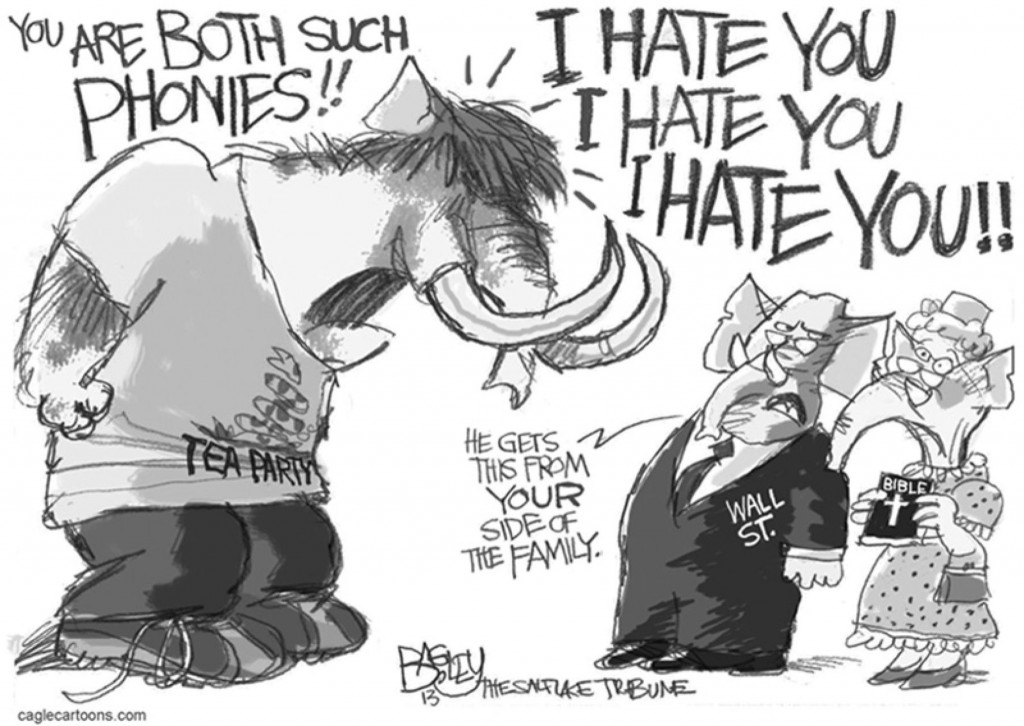

The Tea Party Republicans seem to take pleasure in taunting the corporate lobby.

One can see why Cote might be uncomfortable. Even beyond the debt limit crisis, the Tea Party Republicans seem to take pleasure in taunting the corporate lobby. Texas Senator Ted Cruz—famed for reading Dr. Seuss to Congress during his autumn filibuster—told the Wall Street Journal during his 2012 election campaign, One of the biggest lies in politics is the lie that Republicans are the party of big business. Big business does great with big government. Big business is very happy to climb in bed with big government. Republicans are and should be the party of small business and of entrepreneurs.6

In turn, the organized business lobby— including the Chamber of Commerce, the Business Roundtable, and the National Federation of Independent Business—is starting to express increasingly vocal skepticism toward Tea Party Republicans. They have been joined most recently by other parts of the Republican establishment, including Speaker of the House John Boehner. Still, undeterred by the forces massing against them, the conservatives seem to greet each condemnation as a badge of honor, proclaiming their independence from corporate America and insisting they speak for the entrepreneurs and independent businesspeople—the market visionaries, not the men in gray suits. As one writer for the Weekly Standard put it in fall 2012, “While big business cozies up to Obama once again, Republicans have an opportunity to enhance their reputation as the party of Main Street.”7

The conservatives [insist] they speak for the market visionaries, not the men in gray suits.

At first glance, the widening divide between the Tea Party and the organized business lobby may appear at least mildly surprising. After all, many of the central positions of the politicians associated with the Tea Party—vigilant opposition to the welfare state, contempt for labor unions, advocacy of low taxes, a hatred of regulation—are in fact shared by many of the major business groups, at least to some degree. Moreover, politicians associated with the Tea Party movement have benefited from the lavish donations of several prominent business activists—most famously the brothers Charles and David Koch, but also such advocates as casino mogul Sheldon Adelson. When he was running for office in 2012, for example, Ted Cruz drew donations not only from the Club for Growth (the libertarian business organization which includes developers and regional finance types on its board) but also from a Texas-based banking company, a host of law firms, Wells Fargo, and Goldman Sachs, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. (In 2013, his donors included Berkshire Hathaway—none other than liberal financier Warren Buffett’s holding company.)8 The merest hint of any kind of opposition evokes intense paranoia from some financiers; for example, venture capitalist Tom Perkins warned, in January 2014, of the dangers of a coming American Kristallnacht: “I would call attention to the parallels of fascist Nazi Germany to its war on its ‘1 percent,’ namely its Jews, to the progressive war on the American 1 percent, namely the ‘rich.’”9 The rise of the conservative right has helped lead to a massive enrichment of the American elite, and it is easy to see how and why the entire Tea Party mobilization might be caricatured—as it has been—as little more than the invention of wealthy men.

But despite the many ways in which business has been able to profit from the rise of the right in American politics, and the financial and political contributions that business activists have made to the development of conservatism, the relationship between organized business and conservative activists has long been characterized by ambivalence. From Joseph McCarthy’s denunciations of those born with silver spoons in their mouths, to Barry Goldwater’s earnest plea to reinvent free-market conservatism as a politics of “conscience” rather than crass self-interest, the right’s efforts to claim the mantle of populism have always made it difficult for conservatives to simply trumpet their connections to the very rich.

The entire project of the American right since the New Deal has been to distance itself from the politics of wealth.

The business lobby took on its modern shape in the 1970s. The Chamber of Commerce became far more aggressively activist, while the executives of manufacturing behemoths challenged by that decade’s recession formed the Business Roundtable. But the conservative movement—also then beginning its march toward the White House—had a mixed relationship to the newly confident business organizations. At the time, conservatives such as Pat Buchanan argued that his people had to avoid the perception that they were the “lackeys of the National Association of Manufacturers or the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, volunteer caddies ever willing to carry the golf bags of the ‘special interests.’”10 In contrast to the Social Darwinists of the late nineteenth century, American conservatives since the New Deal have sought to distance themselves from corporate wealth. Sensing this unease, many organized business groups historically have been wary of forming close alliances with ideological conservatives—they want to be able to play both sides of the aisle, and they want to be close to power regardless of which party holds Congress and the White House.

But it has been some time since this division has seemed as stark as it does today. The debt crisis of last fall brought the differences between the Tea Party politicians and the major business organizations into sharp relief. In mid-December 2013, Randall Stephenson, the chairman and CEO of AT&T and the chairman-elect of the Business Roundtable wrote a public letter to the Senate urging support for the budget resolution. The greatest challenge facing the country, Stephenson wrote, is “low economic growth,” and while this might be influenced by many factors, “the inability of the federal government to manage its own finances” was chief among them. “Serial budget showdowns, government shutdowns, and brinksmanship over the full faith and credit of our Nation are damaging the American economy,” the CEO intoned—a clear rebuke to the radical right.11 Meanwhile, Tom Donahue—the fiery conservative head of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce who used to be a supporter of Tea Party types—has denounced the irresponsibility of the conservatives. “When the Tea Party first came out . . . they talked about things that the Chamber very much supports,” he told BuzzFeed.com early in 2014—things like tax policy changes and controlling federal costs. “And then we had people come along with different views . . . and they were the people that didn’t want to pay the national debt [and who shut down] the government.”12

From the standpoint of American business leaders, the notion of doing anything that could call into question the stability of Treasury bonds and the country’s financial system seems like a death wish. It is not as though they are unconcerned with debt. People like Cote have been deeply involved with the Fix the Debt campaign—a business-led effort that seeks to reduce the federal debt, primarily through reform (read: evisceration) of Social Security and Medicare. For the insurgents around the Tea Party, though, the fight over health care reform and the debt limit tapped into a deeper set of issues. For them, the country is already engaged in massively immoral spending that vastly exceeds any real approximation of its wealth. They see the United States as already nearly bankrupt; default would only make this truth literal.

Immigration reform is another obvious area of tension. Conservative Republican leaders such as Ted Cruz have squarely opposed any “path to citizenship” for undocumented people currently in the United States, viewing such immigrants as lawbreakers, people who are fundamentally on the outside of the American community. Yet most of the major business organizations from the Chamber of Commerce to the Business Roundtable prominently support some form of immigration reform. The Chamber, for example, on its website touts its efforts to work with “a variety of odd bedfellows . . . to build a movement for commonsense immigration reform,” expanding the number of visas available to workers of various skill levels and creating some way for immigrants to become citizens—while also strengthening “border security” (a bone to the right).13 The Roundtable goes even further, saying that “it is unrealistic to expect people who have set down roots to leave voluntarily, and large-scale deportation would disrupt the workforce, harm the economy, and cost billions of dollars.”14 None of this has anything to do with social justice; tech businesses want access to skilled foreign workers, agricultural companies would like to be able to hire migrant labor more easily, and many other parts of the economy rely on a low-wage labor force which often comprises mostly immigrants. But it sets the business organizations at odds with the conservatives, whose major goal with immigration reform is to tighten the borders while blocking any system of amnesty or legalization.

Finally, the question of economic inequality may ultimately be another wedge between the business lobby and the Tea Party. The major business organizations have been fairly quiet on the subject of economic inequality. When Donahue gave his annual State of American Business address in early January, he was careful to note that “if” there is any economic inequality, the position of the Chamber is that it can only be addressed through growth: “Freedom for the job creators is going to create more jobs.”15 But there is clearly some sense among more liberal reaches of the business world that the current absurd levels of economic inequality endanger both economic recovery and social stability—as Buffett has put it, it would behoove “this very rich country to have less inequality than we have”—and that perhaps government might play some role in redressing them.16 The conservatives around the Tea Party, of course, reject this notion entirely, seeing any expansion of the welfare state—as in health care reform, no matter how anemic and confused it may be—as a threat to independence, a move even deeper into the mire of debt.

The break between the conservatives and the business lobby is an example of a political Frankenstein—a movement that, once created, ceases to belong to those who helped invent it.

In the past, the business lobby has given tremendous support to the creation of a political agenda centered on lower taxes, less regulation, and cutbacks to the welfare state. This was the project of the Chamber and the Roundtable in the 1970s. But it has also been the center of business politics more recently. As Brendan Greeley has reported in Bloomberg BusinessWeek, it was only a few years ago that business lobbyists such as Donahue were on the barricades denouncing the health care reform bill. Not that such opprobrium was universal; some businesses, especially insurance companies and pharmaceutical firms, were perfectly happy with the new law (especially after the public option was taken off the table). But when it first passed the House in 2010, the Chamber released a statement rejecting the bill in the strongest and most ideological terms: “It marks a major step down the road to a government-run health care system. It will further expand entitlements and explode the deficit, and raises taxes by half a trillion dollars at the worst possible time.” The organization warned that it would oppose the bill through “all available avenues,” and would conduct the largest voter education drive in its history to elect a Congress that would turn back the bill. The Chamber did, in fact, spend $32 million that year on issue advertising, helping to lead to the election of many of the conservatives, who—it seems—took the Chamber’s rhetoric more seriously than it did itself, truly resorting to any means necessary to defund and defeat the law.17 The break between the conservatives and the business lobby (if in fact it endures) is an example of a political Frankenstein—a movement that, once created, ceases to belong to those who helped invent it.

In the mid-1950s, Richard Hofstadter sketched an image of the “pseudo-conservatives” as the true radicals in American life.18 He argued that the people drawn to the McCarthyite cause, the same ones who would become foot soldiers for Goldwater a few years later, were afflicted by an American paranoia that had its roots in the experience of social upheaval and mobility. The very prosperity of the post-war years had the effect of leaving some people behind. These unlucky souls found themselves unmoored and adrift, with no clear sense of purpose or community, only a vague awareness of having been terribly wronged. They became the loyal partisans of the right, which owed its passion and its rigidity to their commitment. Hofstadter suggested a necessary tension between those who found themselves at ease in the world of capital and those who might be drawn into the right. After all, capitalism itself is what stirs up the society, generates the loss, and throws everything into chaos; it was the market that refused to respect any old social values. At the same time, the conservatives claim to represent the true interests of the people—to be the real populists protecting a fragile world ever in danger of dissolution from the fat cats of the Establishment who must be driven out. As Steve Fraser has written, they embody “family capitalism” that links the flourishing of the family, the individual, and the nation to the pursuit of wealth—in contrast to the selfish amorality and soullessness of the global corporation.19

The Tea Party enthusiasts do seem akin to Hofstadter’s frightened rebels, willing to throw the society into chaos to retrieve what they believe to be a deeper order. The original Tea Party mobilization got its start in response to the bailout that followed 2008’s financial crash; its roots lie in antagonism toward the big banks. Yet Hofstadter’s confidence—borne of the certitude of mid-century liberalism—that this world of small proprietors was at heart fearful and defensive and on the way out seems not to have been the case historically at all. As other scholars have shown, Goldwater supporters were frequently financially successful professionals and businesspeople in wealthy suburban communities such as Orange County, people who were actually prospering in the post-war years. Nor is small business an archaic relic; according to the Small Business Administration, the number of small companies has grown by 49 percent since the early 1980s. Perhaps even more important than the reality of small business is the celebration of the norms of entrepreneurship and the market ethos. Increasingly, all employment relations seem modeled on the ideal of the self-employed entrepreneur, with employees reinventing themselves (or being forced to do so) as independent contractors.

The split between the Tea Party Republicans and the business groups suggests the limits of the politics of the free market. As historian Benjamin Waterhouse has shown in his recent study of the development of the business lobby in the 1970s, business organizations such as the Chamber and the Business Roundtable make the implicit claim that they are able to bring together the diffuse concerns of different companies, and to speak in a unified way for the business class. In so doing, the suggestion is always that they advance broader social interests: that they are enlightened paternalists, able to take care of the whole. We all prosper when we make sure that the “job creators” are happy. But (as journalist Doug Henwood has argued) the erosion of older ruling-class institutions and the fierce competitiveness of almost every aspect of our social life today makes it far more difficult for the business lobby to act in any concerted way, with even a pretense of concern for larger social interests. The apparent success of Citizens United offers another example of this underlying difficulty. While the opening of the spigots of cash for elections might seem to privilege the business class as a whole, in fact it mostly enables wealthy individuals to spend lavishly and to do so with little sense of collective purpose. It weakens the clout of the business organizations and even of corporations by expanding the power of phenomenally wealthy individuals.

Ever since the Great Depression businesspeople have been perennially anxious that they have no voice in Washington, that they will need to invent a way to beat back an imminent “attack on free enterprise” (to quote Supreme Court Lewis Powell’s famous memorandum). It is as though their ability to make things happen within their companies never quite translates into the ability to remake the larger society. This fear may be even stronger today than it was during the Reagan years, or during the presidency of George W. Bush. On the one hand, the economic crash of 2008 and the difficulties of recovery have highlighted the sensitivities of the business class and their acute awareness that they cannot control economic events more broadly. But they are also now confronted by the passionate politics of people who also claim to advocate market freedom—although in terms far more absolute than anything most executives would condone. Some of them may feel abashed in the presence of this ideological intensity. After all, the overriding imperative of profit may in part account for why businesspeople always seem to be exhorting other businesspeople of the paramount importance of becoming more politically engaged. Deep down, all of them know that they do not really care—that their own enrichment matters much more than any collective purpose or common vision.

The leaders of the corporate world [have] grown used to working with, even relying on, the government.

In the past, this view was countered by the effort to respond to left critics by defining a socially responsible role for corporations. But today, any such sense of responsibility is defined almost entirely in narrowly economic terms, and it co-exists with a fierce moralism around the high principle of self-enrichment.20 Trying to corral such self-righteous executives and financiers must be a nearly impossible task, although it is what organizations such as the Business Roundtable have always sought to accomplish. It is hardly surprising that it might be slipping out of control. Whatever happens in the current confrontation with the Tea Party, it is no wonder the likes of Tom Donahue and David Cote are growing concerned. As Donahue put it in his early January speech calling for the need to build a “pro-business” Congress, “The business community understands what’s at stake.”21

This article can be downloaded at: http://nlf.sagepub.com/content/23/2/14.full.pdf+html