Bernie Sanders and Progressive Democrats

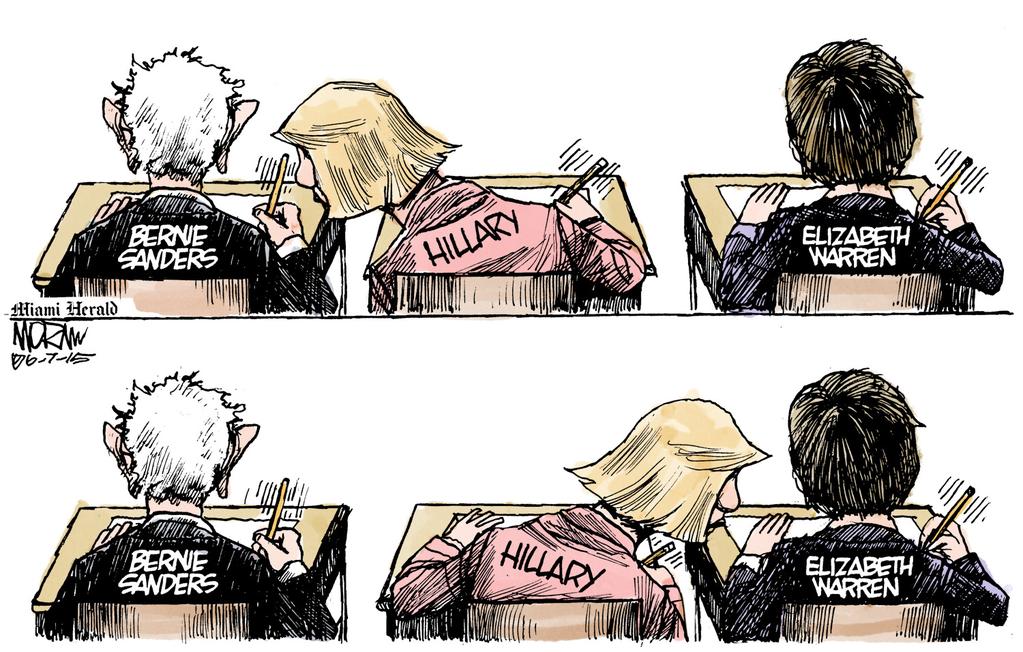

The entrance of Bernie Sanders into the Presidential primary race has created an interesting moment for the progressive movement. We have a triangle with Hillary Clinton, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders all in contention for political leadership. In the middle, trying to decide what to do, are the leaders and activists of social movements, netroots organizations such as MoveOn, and of course the labor movement.

In 2013 I co-founded a political group devoted to making sure that progressives had someone to vote for in the Democratic primary. We called it Ready for Warren, a play on Clinton’s semi-official pre-launch campaign organization. On the one hand, we genuinely wanted Warren to run for President. But even if she didn’t run, support for her might become a rallying point for progressives unsatisfied with the likely coronation of another Clinton.

Last year at the annual Netroots Nation convention, we successfully organized a coming out party for the draft Warren movement, and led attendees in chants of ‘Run, Liz, Run’. There was no comparable energy for Clinton, for all of the obvious reasons: she has bucked the populist base on a series of important issues. These include her support for the invasion of Iraq, support for NAFTA and refusal to oppose the TPP, and her votes for the Patriot Act. But aside from those (evolving) specifics, there is a sense that she is wedded to Wall Street money, allowing her to sound progressive while holding contrary allegiances.

As it becomes ever more clear that Warren is not going to run for president, the same progressive camp that eventually jumped on board the Draft Warren bandwagon is facing the dilemma of what to do about Bernie Sanders. On the one hand, he is actually running. But on the other, the collection of supporters and groups comprising the Warren camp doesn’t want to divide itself or engage in the risks that full-throated support for Sanders would entail.

I find the nature of that divide fascinating, for reasons both personal and political.

As a leader in the Draft Warren movement, I always saw my goal as expanding the space for grassroots political interventions that institutions aren’t well positioned to lead. A classic example of this is Occupy Wall Street. As a phenomenon, it dramatically changed the political narrative of the day, elevating income inequality and the problems of the 99% at a time when cutting Social Security was becoming respectable in Democratic circles.

But it didn’t happen because a well staffed organization wrote a proposal, got it funded, connected with allies, hired a PR firm, and rolled it out. It happened because there was a change in public mood that could only be tapped by outsiders following a different logic.

One expression of this tension is the well known counter-position of Occupy activities to electoral political activity. Outside of a few small exceptions, Occupiers didn’t jump to support candidates as part of that movement. Many believed that the formal political layer encompassing elections and politicians is corrupt, while local, grassroots interventions taking place outside of formal institutions are the only way to advance a radical agenda.

But over time, leaders of the Occupy diaspora came to realize that the relationship between elections and radical politics is more complicated. We needed more formal institutional access so our voice would be heard in more places. Meanwhile, we saw politicians, unions and staff led organizations piggyback on our messaging, sometimes in ways that felt exploitative. We lacked a vehicle to ‘be in the room’ during peak moments of citizen and voter engagement, unless it was ‘one of us’ as an employee or freelance contractor for one of those funded organizations.

Ready for Warren

Ready for Warren was inspired by the Occupy ethos. Instead of waiting for permission from more established institutions, we created the buzz and groundswell that would spark a year long media moment. For the first year of our existence, no other organization would express support and no celebrity spokesperson emerged to stand with us to call for Warren to run for President. This was true even though it was obvious that the progressive base loved what we were doing, as evidenced by the popularity of our hashtags, comments from attendees at Warren book signings, and press reports reporting on the ‘draft Warren movement’ that was just us.

Then, in late 2014, MoveOn and Democracy for America announced that they would poll their organizations for approval to start a new partnership in support of drafting Warren. The Working Families Party in New York followed suit, along with movement figures ranging from Zephyr Teachout to Van Jones to Larry Lessig.

What happened was that supporting Warren became safe for institutional actors. Or rather, refusing to support the Draft Warren movement was starting to look like a missed opportunity, because of the grassroots support from members of progressive groups. The fact that she was not running, coupled with her intense popularity, created a perfect storm of less risk and more impact. One of the ways we can see that is the frequency of fundraising emails sent by large internet lists. MoveOn, Democracy for America, and the Progressive Change Campaign Committee have used Elizabeth Warren’s name in fundraising emails a lot over the last twelve months, generally in support of campaigns run by those organizations.

The Draft Movement Moves On

As this piece was being written, the ‘Run Warren Run’ effort by MoveOn and DFA has been “suspended.” It’s leaders write: “Although Run Warren Run may not have sparked a candidacy, it ignited a movement.”

Can we call such efforts a “movement”? It’s a tricky question. I often use that word to refer to bottom-up groundswells that drive an agenda for an issue or set of issues. Politicians often refer to support for themselves as part of a movement, usually in a self-serving way that only makes sense in the context of a political campaign, and only to actual supporters. In the case of Warren, however, the movement is less the result of masses of people rallying to her anti-bank stance, and more the result of countless progressives seizing on her outsider-with-power status to bring a suite of issues to the public’s attention. On balance, I would say that support for Warren has been more ‘movement-y’ than almost any comparable effort since Howard Dean’s campaign in 2003.

While Ready for Warren has run efforts as recently as May to press her into running, the enthusiasm for such activities has definitely declined. My impression is that most Draft Warren supporters have accepted that Warren won’t run, unless there is some kind of self-inflicted Clinton meltdown. Our impact on that is non-existent. But meanwhile, Clinton has been adopting more populist positions lately. Slate’s Josh Voorhees reports:

In the two months since Hillary Clinton officially launched her presidential campaign, the overwhelming frontrunner for the Democratic nomination has moved left early and often. She’s made a forceful case to reform the criminal justice system, expand President Obama’s immigration overhaul, establish universal and automatic voter registration, and make same-sex marriage a constitutional right. Her leftward turn continued this past weekend with her call for a pay hike for low-wage workers, the latest sign that she’ll try to use economic equality as a populist calling card in 2016.

A skeptic might ask: wouldn’t Clinton have changed her positions to sound more like Warren in any case, as a reflection of the Democratic base’s shift towards populism? We’ll never know for sure, but the last year has seen many instances where Elizabeth Warren confronted fellow Democrats and President Obama and used those moments to build her influence. (For example, the Antonio Weiss nomination to a senior Treasury position was scuttled by Warren’s efforts, her Citibank speech against a spending bill weakening Dodd-Frank, and her leadership in the fight against the TPP.) To my knowledge, we’ve never seen such a well coordinated movement to back one specific politician (who isn’t the President) against others in the Democratic Party, when that politician isn’t even running for anything.

Shifting Strategy

Over the course of these fights, and as the chances of Warren entering the race declined, the Draft Warren movement shifted in the direction of influencing the debate, as opposed to drafting Warren. The ‘Warren wing of the Democratic Party‘ was focused on building agenda setting power without the risk of backing a Clinton challenger. Progressive institutions got to have their cake and eat it too.

This strategy makes a lot of sense. Vast amounts of money are going to be raised and spent on the general election. Careers are made and lost based on who gets on the right campaign staff at the right time. Relationships forged during the primary are folded into the general election. If Clinton wins, everyone on the right side has a chance to move up a slot. Thousands will be promoted to Administration jobs, and thousands more get the recently vacated jobs.

Beyond the individualistic career motivations, there are the raw politics of it. Who will have access to the next White House? Organizations on the wrong side of the fence have legitimate concerns about their effectiveness in the next term. This is true not only for corporate interests we might object to, but also for genuinely progressive labor unions and grassroots movement building organizations.

Bernie Sanders’ entrance into the race provides an opening for grassroots energy again, in the vein of Occupy and the early Draft Warren movement. The campaign offers a chance for entrepreneurial organizers who lack institutional power to push forward, past more risk-averse institutions and individuals (who may share their values and personal affinity for Sanders). Furthermore, this zone of entrepreneurial organizing efforts on the left of the Democratic Party, and to the left of the Democratic Party includes actors who are voicing a far more comprehensive critique of capitalism than would otherwise exist. This vibrant and open membrane between anti-capitalist and Democratic politics includes remnants of Occupy Wall Street, Democratic Socialists of America, and even Kshama Sawant’s Socialist Alternative, which has given guarded support for Sanders.

The Grassroots-Led Option

Because Sanders won’t have enough money to run a massive, staff heavy 50 state campaign, a large fraction of the work will be done by volunteers operating with very loose relationships to the official campaign. The organizations eager to support this effort are small, poor, and few. There won’t be a SuperPAC corralling other entities and c4’s in the background. This means that self-motivated and self-organized activists will be taking the lead, including a higher proportion of people who lack experience and visibility as Democratic operatives at the national or local level, but who come from social movements that prioritize grassroots initiatives.

The rise of social media and inexpensive organizing tools make it more possible than ever for people power to successfully stand up to money power. This can lead to a divide between the leadership class of paid staff and large donors, if and when their nominal supporters ‘move on’ to active support for the Sanders campaign. For example, in the days after Run Warren Run suspended its campaign, the comments on their Facebook page where heavily in favor of pivoting towards Bernie Sanders. Such lobbying won’t be enough to make it so, but over time grassroots-driven organizations must be aligned with their supporters and donors, or they won’t be able to accomplish their goals.

Of course, none of this means that supporters of Bernie Sanders have the wind at their backs, or that we can feel confident about having a declared democratic socialist in the White House in 2017. But it opens up a particular kind of opportunity that we haven’t seen since Howard Dean and Dennis Kucinich ran for President in 2003-4.

A window opens when Democrats have an open presidential primary and get to hash out very publicly what they believe in and why. That energy can unleash new organizations and alignments, as happened with the birth of DFA and Progressive Democrats of America in 2004. Social media is weakening the power of Beltway pundits to narrowly set the boundaries of respectable debate, allowing issues that are genuinely popular to break through and express themselves in the primary process.

Left Wing of the Possible

Electing Bernie Sanders won’t be easy. But remapping ‘the left-wing of the possible’ (to use a Michael Harrington phrase) is within reach, changing the political landscape for our issues and associated social movements going forward. That remapping was in fact one of the most visible and least arguable of the Occupy Wall Street achievements, but it hasn’t been very deep. Grassroots and social movement energy is rising, but more often than not isn’t at the table when decisions are made.

This can change. A different kind of politics is possible, as exemplified by the rise of Podemos and affiliated municipal level coalitions in Spain, and Syriza in Greece. It’s feasible for us to imagine modified ‘general assemblies’ at the local level to bring to the surface what voters want, and then mapping that to the positions of candidates. This means returning to the problems of electoral politics, while reversing the usual priorities. Where mainstream politics puts the candidate at the top, we can put communities, movements, and issues at the top, and then introduce a relationship to candidate we can hold accountable.

I’m well aware that this isn’t an unusual approach. Community organizing groups have done similar work for generations. But we have a cohort of activists with Occupy experience eager to make this pivot and to apply the lessons of the last few years to have an impact measured in votes. It can break free of the bonds of paid staffers and gatekeepers who form the backbone of traditional campaigns, turning the relative weakness of Sanders’ campaign into an opportunity to change the model, making it more democratic in style and practice, and more accountable.

State level, citywide, and constituency-based ‘councils’ of Sanders supporters are likely to emerge without the campaign having the power to direct them or change the leadership. In contrast to the Clinton or Obama campaign structures, there won’t be the carrots of jobs or influence to maneuver grassroots activists intent on building those structures with a post-campaign future in mind. And nothing is stopping those councils from continuing to operate past the normal expiration date of the state primary or general election.

While none of this will dramatically change the contours of the 2016 race, it can amplify Sanders well past his anticipated $50 million budget, and it has the potential of reverberating well past election day. This represents a strengthening of all our issues: climate justice, bank reform, raising minimum wages, state level single payer healthcare, community control of police, more support for coops and union organizing efforts, and a shift in power from staff-driven political entities, to ones accountable to a nonprofessional mass base.

Won’t it be something, to take some of that raw inchoate populist energy and turn it into real world political power without having to filter it through the lens of countless professional staffers, celebrity donors, and field building foundations? I certainly think so – and I’m not alone.

Charles Lenchner is a co-founder of People for Bernie, an Occupy inspired grassroots effort in support of the Bernie Sanders campaign. He is also a co-founder of Ready for Warren, which has spun off a new pro-Sanders entity: Ready to Fight.

The fact that she supports a corporate monopoly for testing and destroying schools seems to have no effect on the so called “Ready for Warren” movement. We have been under occupation of corporate education deform, especially under Obama,and you folks seem to have no problem with Warren’s support for continued corporate control of education.