We Believe that We Can Win!

“On the Contrary”

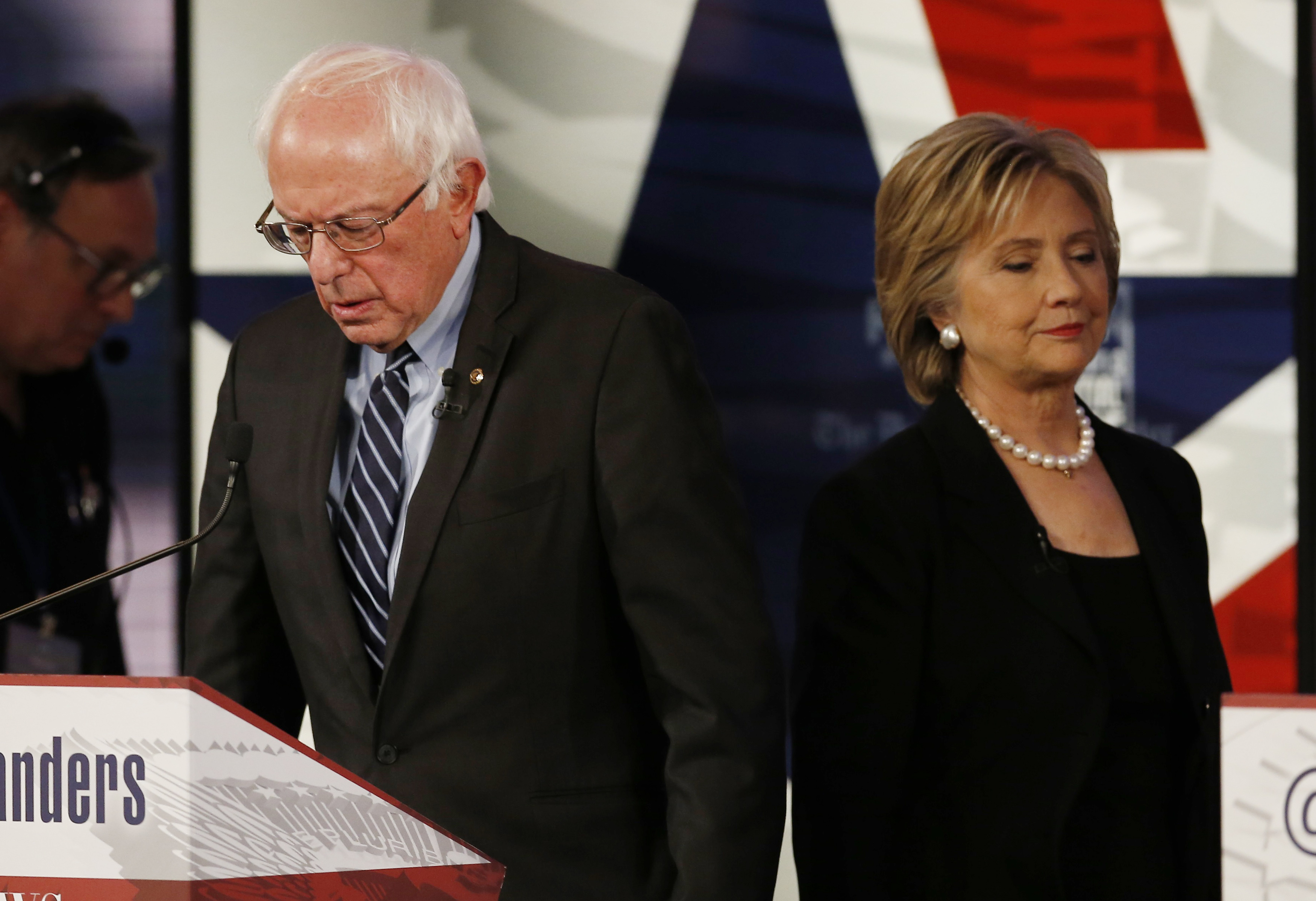

Did the Sanders Campaign Represent a Missed Opportunity for the U.S. Labor Movement?: A Debate

As our readers know, the labor movement was divided during the Democratic Party primary season over whether to support Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders for the Democratic presidential nomination. We invited contributions from both sides to debate those differences. Larry Cohen, past president of the Communications Workers of America argued on behalf of the Sanders option, and Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, together with Leo Casey, president of the Albert Shanker Institute, argued on behalf of the Clinton nomination. They delivered their initial arguments in early September and then responded to each other. Both authors assumed, as many readers also did, a Clinton victory. When the election results came in, Randi Weingarten and Leo Casey asked to rewrite their essay in order to take fuller account of the outcome of the election. Larry Cohen agreed to this arrangement. However, he elected to leave his essay as originally written. He has added a brief addendum that also takes account of the election results. Since Weingarten and Casey withdrew their original contribution, it no longer made sense to publish the replies each had written in response to each other. Readers should keep in mind that the main part of Cohen’s contribution was written without knowing how the election would turn out, while the Weingarten and Casey essay was written after that outcome had been decided.

When Bernie Sanders began his quest for the presidency in May 2015 in Burlington, Vermont the democratic political establishment either ignored or opposed him. Hillary Clinton had been running for years and had hundreds of staff and commitments from hundreds of super delegates. Labor leaders were used to being part of that establishment as well. Although clearly quite different from the Republican Party establishment, labor leaders regularly mingle with Democratic Party leaders and big-money party funders.

“Bernie can’t win,” they repeated to each other over and over. But actually when they said Bernie can’t win, what they really meant was that working-class people can’t win. Sadly, in 2015 most labor leaders had come to believe the legislative priorities long supported by many unions ̶ like single-payer health care, stopping unfair trade deals, or making public higher education affordable ̶ and couldn’t form the basis for a realistic political program for presidential candidates. Ironically, Bernie Sanders’ campaign moved Hillary Clinton ̶ the establishment candidate who sought to convince primary voters she was more able to win ̶ much closer to those and other positions once considered radical.

Far too many labor leaders have long believed that our political action programs are a defensive tactic, or at best on rare occasions a means to achieve incremental advancement, like the Affordable Care Act. It’s easy to criticize such behavior but it’s not new, and with U.S. collective bargaining coverage down by nearly two-thirds in 40 years to just under 12 percent, it’s not surprising. But for those of us who link that slide to the lack of an aggressive political program challenging the fundamental aspects of our economy, that explanation is not sufficient.

There are disparate strategies within labor. Sectoral differences among building trades, government, industrial, and services lead to important differences in political strategy. For government and education workers, the link to elected officials is obvious. While those elected officials are not supporting political revolution, they are adopting budgets that determine whether and how union members work, and often their pensions and health care as well. For many unions, the distinction between lobbying and collective bargaining is very small. Political fundraising from members by these unions is aimed at influencing these bread-and-butter employment issues not the larger issues confronting working families as a whole.

Before Bernie Sanders announced his candidacy hundreds of the congressional and other super delegates who create the political frame for public sector and other unions had already announced support for Hillary Clinton. Breaking from the party establishment would not have been easy for those public-sector unions particularly at the national level. Additionally, political risk aversion is part of the calculus. In the summer of 2015 there was an overwhelming likelihood that the Supreme Court would eliminate the agency shop in the Friedrichs case. As it turned out only the death of Justice Scalia led to the tie vote in that case that left the agency shop in place for those states that permitted it. Practical politics, even at the presidential level, trumped movement-building, transformational politics.

A similar logic often applies to building trades unions, heavily dependent on government- funded projects. Candidates more likely to win, sometimes Republicans as well as Democrats, often get the nod based on funding commitments for public infrastructure.

And similarly for private sector workers from regulated industries, union political endorsements often hinge on candidates’ records on regulation not on broader concerns. Airline and rail workers with high degrees of unionization often make political calculations based on very specific industry issues.

Many national unions, including auto, steel, bakery, letter carriers, teamsters, and electricians, did not make a presidential endorsement until mid-2016 when the primaries were over or nearly over. As a result, there was not a formal AFL-CIO endorsement until just weeks before the Democratic National Convention.

Several national unions, including Communications Workers of America, National Nurses United, American Postal Workers Union, and Amalgamated Transit Union did endorse Bernie Sanders by the end of 2015. Eventually they were joined by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (West Coast dockworkers), United Electrical Workers, the National Union of Healthcare Workers and more than 100 locals from other national unions that either did not endorse or had already endorsed Hillary Clinton. Tens of thousands of active union members formed a national network, “Labor for Bernie” and worked within their unions and in their communities to support Bernie in their state’s caucus or primary.

In most cases, local unions that supported Sanders did not face retribution from their national union. This level of tolerance for local political autonomy is critical moving forward. It is one thing for a national union, through its executive board, to make an endorsement; it’s quite another thing to demand local adherence without a membership vote or formal local input.

Given all of the above, the remarkable outcome was the outpouring of support for Sanders from active union members. Local leadership combined with the national unions that did endorse Sanders, rather than the disappointment with the public sector, education, building trades, and other unions that were early Clinton endorsers.

This support for Sanders translated into strong union majorities in Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, and several other states.

Union support was also an important part of the Sanders campaign’s narrative. Fighting the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and pointing out the harm continuing from the U.S. trade regime that started with NAFTA was central to the campaign. In Chicago, bakery workers at Nabisco, facing the shutdown of the Oreo cookie line at their south side plant resulting from outsourcing of production to Mexico rallied and held news events weeks before the Illinois primary. In Michigan, workers held a press conference detailing what had happened to their families decade after decade as American Axle & Manufacturing, General Motors and others shut down their plants seeking cheaper labor in Mexico and other nations. As Senator Sanders told it, Flint’s hardships originated with GM shutdowns in what had been their hometown. Lead-contaminated water followed years of skyrocketing unemployment, and declining tax revenues in a city that in the early 1960s had been among America’s richest.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of union support came from United Steel Workers (USW) Local 1999 in Indianapolis. A few months before the Indiana primary, United Technologies (UT) announced that it was moving production of its Carrier furnaces to Monterrey, Mexico after fifty years in Indianapolis. Management held an all-hands-on-deck meeting in the plant breaking the news that it would close in about a year. Local President Chuck Jones decided that it was time to fight back and not wait for negotiations over the consequences of the closing. Chuck and his members decided that the upcoming Indiana primary provided an opportunity to join this issue with the election and ask the presidential candidates for help.

Sanders answered the call and fighting UT became a centerpiece in the Indiana primary. Just days before the primary, Sanders spoke and joined a march through the city protesting the closing, that included USW officials and AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka. Chuck Jones and most Local 1999 members supported Sanders as he attacked our government for awarding billions in U.S. contracts to UT and then doing nothing when the company announced that 2,000 jobs would be going to Mexico solely because of much cheaper labor and virtually no regulation.

We could certainly moan about labor’s lost opportunity, and had the labor movement united behind Sanders he would have been the nominee and very likely the President. However, the real lesson of the last year is our need to build a broader and more powerful movement for change. For years to come, individual labor unions will most likely pursue conflicting political strategies. But those of us who believe that we need a new political movement demanding real change, we have now built the largest movement for that change in decades. It is messy and still uncertain, but the political revolution of Bernie Sanders, now called Our Revolution will forge ahead endorsing candidates and ballot measures, fighting the TPP, and struggling to unite and expand on the 13 million voters who supported Sanders.

No one would claim that Our Revolution, the successor to Bernie 2016, is the only path forward. There are many other attempts to build this movement. We must do a much better job of uniting racial, economic and environmental justice movements. But the question for active union members is more about the future than the past. Do we believe that we can win? Are we ready to build a political movement that works inside and outside the Democratic Party without attacking ourselves? Can we unite around defeating the Trans-Pacific Partnership and other destructive policies and in doing so show that we can win?

We learned from Bernie’s campaign that real change is possible. We learned that many Americans are not afraid to consider themselves workers, and not just middle class. We learned that we can fight for racial justice as well as economic justice and that doing both at the same time makes us stronger. But mostly we learned that it all starts by actually believing and acting like “We Can Win.”

Addendum:

First, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by nearly two million and in any other democracy she would be President elect. The barriers to a 21st century democracy for our nation range far beyond voting rights and big money in politics.

Second, Obama far out polled Clinton in key working class counties in PA, MI, WI and even small towns in Maine. Those who look for racism as the key variable in Trump’s win need to look much deeper at voting results rather than projecting simple answers. The destruction of manufacturing jobs through public policy neglect and bad trade deals is a major factor explaining Clinton’s loss in those states and a major problem for Democrats who ignore it.

Recent leaks of emails from the DNC and the Clinton campaign chair, indicate that the party elite were improperly involved assisting the nomination of Hillary Clinton in every way possible, and that the Super PACs supporting the Clinton campaign were willing to use divisive and even hateful tactics.

Bernie Sanders is now among the most popular electeds in our nation. His narrative of working class unity and his focus on free higher education, better health care, peace and justice, fair trade not trade for investor profit, and infrastructure aimed at communities of color and other impacted communities is the basis for Our Revolution, the successor to his campaign, as well as other progressive organizations.

So as we go forward, are we willing to organize around our values, including in primary elections, rather than accept the view of the Democratic Party establishment about who can raise money and therefore who can win? We can’t just speak out about Citizens United and then defer to those who use every opening to dominate nominations with their dollars.

The Democratic Party itself badly needs structural reform if Democrats are to win the support of working class voters. There needs to be a real priority on registering millions of voters of color and others trapped by our outrageous voter registration procedures while at the same time we need to fight for automatic voter registration as Alaska just adopted in this election. We also need to be ready to support independent candidates when they represent our values. We need to use ballot measures to promote democracy as even this year most pro democracy ballot measures won across the nation.

President Trump will immediately have the two openings necessary to control the NLRB, and begin to roll back the last eight years of Board decisions. Likely anti-collective bargaining legislation in the Congress and the States will put us on defense again. But this time can we not only resist, but also build a political movement that speaks to our dreams and aspirations, so that we are campaigning for our values as we fight for the future?

Link to Weingarten and Casey article in series

–http://newlaborforum.cuny.edu/2016/11/22/on-the-contrary-american-labor-and-the-2016-elections/