Modern Art/Ancient Wages

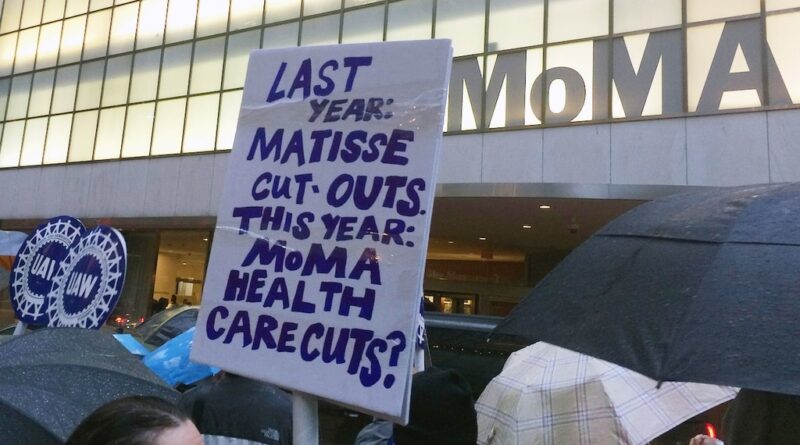

Caption: Vintage MoMA — Museum of Modern Art workers demonstrate in 2016.

A half century ago, in 1971, staffers at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) organized an independent union known as PASTA, the Professional and Administrative Staff Association. With its initial contract, PASTA became the first union at a major art museum to represent a “wall-to-wall unit” of curators, art handlers, administrative personnel, educators, and members’ services staff. In part, PASTA grew out of political and social ferment in the 1960s and 1970s, at a time when newly minted arts and cultural organizations (the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition was one) were agitating for change at MoMA and other major arts institutions, including New York’s Whitney Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Above all, however, the driving force for unionizing at MoMA was to raise the low wages offered to cultural workers in exchange for “prestige”—the privilege of working at an elite arts institution. Even today, an assistant curator at a major museum in a big city can earn as little as $40,000 a year. Into the bargain, that same curator would be expected to have a PhD or be in a doctoral program.

By the mid-1970s—after two contract strikes—PASTA affiliated with District 65 (later District 65-UAW [United Auto Workers]), a union known for its progressive stance on social and political issues as well as bread-and-butter union issues. The union at MoMA became a cornerstone of District 65’s unit of technical, office, and professional workers, now Local 2110 of the UAW. PASTA’s motto then, “Modern Art/Ancient Wages,” remains a rallying cry today as a wave of museum organizing across the country has gained momentum over the last two years.

In July 2021, workers at the Whitney Museum won union representation by a vote of 96-1, and on August 15, a unit of about 130 workers at the Brooklyn Museum voted overwhelmingly for the union. More than fifteen other museums and arts institutions nationally are currently at different stages of organizing into Local 2110. Some, like the New Museum and the Tenement Museum in New York, already have signed agreements. Others, like Mass MoCA (Museum of Contemporary Art) are in negotiations. But bargaining for a first contract can be tough. In November, workers at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston called for a one-day strike to push stalled negotiations along. A petition to hold a union election at the Guggenheim Museum has been filed with the National Labor Relations Board. The American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees (AFSCME) is another union actively organizing museum workers. In August 2021, 89 percent of eligible employees at the Philadelphia Museum of Art voted to join AFSCME. That same month, employees at the Art Institute of Chicago announced their intention to organize into AFSCME. In October, workers at the Baltimore Museum of Art did the same. Maida Rosenstein, the president of Local 2110, attributes this surge in organizing to a number of factors, including a striking increase in younger workers. These thirty-somethings, she says, skew left, have a heightened consciousness of wage inequality, and are generally more pro-union. “Thank you, Bernie,” Rosenstein says. And, because the very wealthy members of museum boards are constantly in and out of the galleries, museum workers see economic and social inequality up close and personal. As Karissa Francis, a lead rank-and-file organizer at the Whitney, put it, “In museum work, there’s a real sense of ‘Upstairs, Downstairs’—a sense of us vs. them.”

While the bottom line in museum organizing is still wages, job security has become an urgent concern. Since the pandemic began in 2019, museums nationwide have laid off or furloughed hundreds of full- and part-time workers. At the Whitney, layoffs came in two stages, affecting nearly a hundred out of a total of four hundred employees. Francis, who works in the Member Experience Department, says, Pandemic layoffs across institutions really shook us up. They were a huge wake-up call. We realized we are all on shaky ground and we started to wonder, “Where do I go? Do I go to another institution where I could be laid off just as easily?”

Museum workers—like workers in every other sector—want a say in determining their working conditions, and Karissa Francis is looking forward to negotiations for a first union contract at the Whitney. She thinks of the union as a great leveler: “In a shop where elitism might otherwise be pervasive, being open about salary and job conditions—sharing information—breaks down barriers and inspires solidarity.”

Author Biography

Kitty Weiss Krupat is a long-time organizer and an associate editor of New Labor Forum.